US Special Envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan Richard Holbrooke’s breezy suggestion that we will know what success in Afghanistan is “when we see it” caused something of a stir in the blogsopshere today. The remarks were made at a Centre for American Progress (CFAP) event in Washington yesterday in response to a question from the floor. The event was conceived as an opportunity for Ambassador Holbrooke and his Interagency Team to settle the nerves of a sceptical foreign policy community by laying out the principles underlying their new ‘whole of government’ approach. In view of what has unfolded, the effort now looks to have been largely counterproductive.

US Special Envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan Richard Holbrooke’s breezy suggestion that we will know what success in Afghanistan is “when we see it” caused something of a stir in the blogsopshere today. The remarks were made at a Centre for American Progress (CFAP) event in Washington yesterday in response to a question from the floor. The event was conceived as an opportunity for Ambassador Holbrooke and his Interagency Team to settle the nerves of a sceptical foreign policy community by laying out the principles underlying their new ‘whole of government’ approach. In view of what has unfolded, the effort now looks to have been largely counterproductive.To be fair to Holbrooke, America was already turning sour on the mission in Afghanistan. The debate has become increasingly fractious over the last month, with the most persistent questions centring upon the need for an exit strategy. And that mood was widely reflected in the questions from the floor. Rather than allay people’s fears, however, his comments appear to have compounded them, with commentators seizing on the remark as further evidence that the policy is in trouble. Mark Lynch, Robert and Renée Belfer Professor of International Relations at Harvard University Stephen M. Walt and Katherine Tiedemann over at foreignpolicy.com and Ian Leslie at the excellent Marbury blog between them pretty much capture the mood, each suggesting that the mission lacks strategic focus and warning of the danger of mission creep, with Walt and Lynch in particular striking an increasingly sceptical note.

Alongside this flurry of criticism, we find the more considered objections of committed sceptics Michael Cohen at Democracy Arsenal and Richard North at Defence of the Realm. I am a great admirer of Richard North. He does important work documenting equipment shortages and failures in procurement policy. Where I have problems is when he tries to draw wider strategic conclusions from it. He has amassed a considerable body of evidence pointing to a devastating catalogue of failure and mismanagement at the heart of the British mission in Iraq and his work is vital reading for that reason alone. It does not, however, pose any serious strategic questions. Fundamentally, his observations are confined to the tactical level and part of the normal ‘lessons learned’ post-conflict debate. Nothing in his work supports his wider argument that we have suffered a strategic defeat in Iraq, or that we are likely to in Afghanistan. I simply do not see evidence for that kind of assessment. Similarly Michael Cohen: I consider his never less than excellent analysis essential reading and yet nothing in his work really addresses the core strategic dilemmas.

Alongside this flurry of criticism, we find the more considered objections of committed sceptics Michael Cohen at Democracy Arsenal and Richard North at Defence of the Realm. I am a great admirer of Richard North. He does important work documenting equipment shortages and failures in procurement policy. Where I have problems is when he tries to draw wider strategic conclusions from it. He has amassed a considerable body of evidence pointing to a devastating catalogue of failure and mismanagement at the heart of the British mission in Iraq and his work is vital reading for that reason alone. It does not, however, pose any serious strategic questions. Fundamentally, his observations are confined to the tactical level and part of the normal ‘lessons learned’ post-conflict debate. Nothing in his work supports his wider argument that we have suffered a strategic defeat in Iraq, or that we are likely to in Afghanistan. I simply do not see evidence for that kind of assessment. Similarly Michael Cohen: I consider his never less than excellent analysis essential reading and yet nothing in his work really addresses the core strategic dilemmas.To get a grip on these we need to turn back to the arguments of Stephen Walt. Walt comes out of the grand tradition of American realism. Centred around the work of theorists such as Morgenthau, Niebuhr and Waltz - although more latterly John Mearsheimer - the tradition of American realism is a venerable one, of long standing. It is supported by a voluminous literature, backed up by a sophisticated theoretical edifice and powered by passionate advocacy, and yet it is a fundamentally flawed doctrine. It regards as axiomatic the idea that the internal characteristics of states do not affect their outward behaviour. From this perspective, behaviour is structurally determined and so it is not to the internal make up of states that policymakers should look when formulating strategy, but rather to structural factors such as the balance of power.

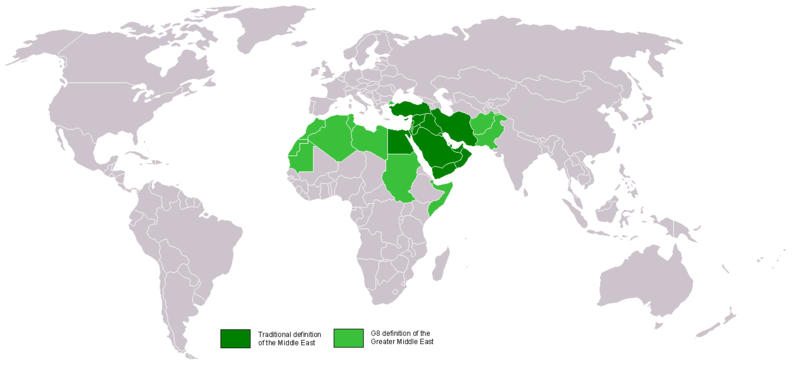

As a major premise, this was always dubious. In the first decade of the 21st century, it is positively reckless. Anywhere we look in what we might call the ‘Greater Middle East’ - that great arc of instability stretching from the Horn of Africa up to the Central Asian Muslim Republics (Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan) - we see the same pattern. Alongside a toxic mix of ethnic, tribal and confessional hatreds we find a horribly dysfunctional state system. Wherever we look, politics is played out against the backdrop of a colossal failure of governance. The threats in the region – be it the threat of balkanisation along tribal, ethnic and confessional lines, of gangsterism and warlordism, or the threat from supranational identities like revolutionary Islam and Arab nationalism – all of them emerge out of the millennial failure of the state. And no amount of elegant structural theorising is going to change that.

As a major premise, this was always dubious. In the first decade of the 21st century, it is positively reckless. Anywhere we look in what we might call the ‘Greater Middle East’ - that great arc of instability stretching from the Horn of Africa up to the Central Asian Muslim Republics (Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, and Azerbaijan) - we see the same pattern. Alongside a toxic mix of ethnic, tribal and confessional hatreds we find a horribly dysfunctional state system. Wherever we look, politics is played out against the backdrop of a colossal failure of governance. The threats in the region – be it the threat of balkanisation along tribal, ethnic and confessional lines, of gangsterism and warlordism, or the threat from supranational identities like revolutionary Islam and Arab nationalism – all of them emerge out of the millennial failure of the state. And no amount of elegant structural theorising is going to change that. What does this mean for US grand strategy? Above all, it means that the old diplomacy is no longer enough. We need to go beyond power balancing. In the Middle East it means undercutting the appeal of regional identities like revolutionary Islam and secular Arab nationalism in favour of the nation state without unleashing forces like ethnic and tribal rivalries that threaten to outstrip the pace of reform and engulf it. It is a delicate balance to strike and a high-risk strategy. Of course, it assumes that Western policy is capable of that kind of nuance and means avoiding clumsy interventions like those undertaken in the past in places such as Suez and Iran. Does it mean turning the region into a "high GDP nirvana" and bringing "free wireless" to the entire world as Mark Lynch facetiously put it? No. There is no universal template that can be applied and even if there were, it would not look like that. The AfPak phase of the mission is scheduled to wind down when Afghanistan crosses the threshold into something approximating self-sustaining growth, when the government in Kabul is able to effectively police its own borders, and when movement across the Durand Line no longer poses a threat to the integrity of the Pakistani state.

What does this mean for US grand strategy? Above all, it means that the old diplomacy is no longer enough. We need to go beyond power balancing. In the Middle East it means undercutting the appeal of regional identities like revolutionary Islam and secular Arab nationalism in favour of the nation state without unleashing forces like ethnic and tribal rivalries that threaten to outstrip the pace of reform and engulf it. It is a delicate balance to strike and a high-risk strategy. Of course, it assumes that Western policy is capable of that kind of nuance and means avoiding clumsy interventions like those undertaken in the past in places such as Suez and Iran. Does it mean turning the region into a "high GDP nirvana" and bringing "free wireless" to the entire world as Mark Lynch facetiously put it? No. There is no universal template that can be applied and even if there were, it would not look like that. The AfPak phase of the mission is scheduled to wind down when Afghanistan crosses the threshold into something approximating self-sustaining growth, when the government in Kabul is able to effectively police its own borders, and when movement across the Durand Line no longer poses a threat to the integrity of the Pakistani state. The same principle applies throughout the Middle East. The current religious awakening is driven in large part by dissatisfaction with the corruption and impotence of the secular authorities and so again, the optimal course is to weaken the grip of confessional identities, bring some measure of representative government to the region, and reinforce the state system. The principle is being applied in a very direct way in Iraq, of course, the intervention there being a crucial test for the new diplomacy. If the new governance mechanisms do not deliver real benefits on the ground in terms of basic security and services, the population will not embrace them and so this is the real test of success, the real set of benchmarks. If commentators are looking to develop a set of metrics they should look to the civilian effort, rather than solely at the military side of the equation. They would be greatly helped in this endeavour if the top US diplomat in the region could manage to bring just a little more eloquance to his advocacy. "We'll know it when we see it" just isn't good enough.

The same principle applies throughout the Middle East. The current religious awakening is driven in large part by dissatisfaction with the corruption and impotence of the secular authorities and so again, the optimal course is to weaken the grip of confessional identities, bring some measure of representative government to the region, and reinforce the state system. The principle is being applied in a very direct way in Iraq, of course, the intervention there being a crucial test for the new diplomacy. If the new governance mechanisms do not deliver real benefits on the ground in terms of basic security and services, the population will not embrace them and so this is the real test of success, the real set of benchmarks. If commentators are looking to develop a set of metrics they should look to the civilian effort, rather than solely at the military side of the equation. They would be greatly helped in this endeavour if the top US diplomat in the region could manage to bring just a little more eloquance to his advocacy. "We'll know it when we see it" just isn't good enough.